Passion and Revolution: Delving into the French Romanticism of the 19th Century

Exploring an Era of Intense Emotions and Artistic Upheavals

Welcome to our exploration of 19th-century French Romanticism, an era of passion and revolution in art. This period marks a turning point in artistic expression, where primordial emotions and the quest for individuality take center stage.We'll look at emblematic works of the movement.

How did Romanticism in France revolutionize the perception and artistic representation of nature, the individual and society in the 19th century?

1. Romanticism, a mirror of the soul Romanticism is distinguished by its emphasis on emotion and imagination, breaking with neoclassical rigor.

A. Romanticism: a new conception of art

Romanticism emerged as a response to the Enlightenment, an era marked by the primacy of reason and science. This movement favors the expression of emotions, feelings and imagination. Initially appearing in Germany and England in the late 18th century, it spread to France and the rest of Europe in the early 19th century, influenced by political, social and economic changes, notably the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars.

Characterized by individualism, mysticism, intense passions, nostalgia and an attraction to majestic nature, Romanticism values emotions, imagination and nature as inexhaustible sources of inspiration. Romantic painters express their deepest emotions and create unique moods through the use of vivid colors, striking contrasts and expressive forms. They also celebrated exoticism, folklore and history, drawing inspiration from national narratives and popular legends. Imposing, fast-moving landscapes become the backdrop for dramatic scenes and historical events. This movement also emphasized individual genius and creativity, elevating artists to the status of unique figures capable of transcending the conventions of their time.

B. The role of nature in Romanticism

In Romanticism, nature plays a predominant role. It is not merely a setting, but becomes a central actor, rich in symbolic meaning.

Romantic painters saw nature as a muse and a refuge, in stark contrast to the hustle and bustle of contemporary society. They are drawn to sublime, untamed landscapes, reflecting both natural grandeur and splendor, while awakening intense feelings in the viewer.

To convey these emotions, they turn to elements of nature such as craggy mountains, dense forests, mighty waterfalls, violent storms and colorful twilights, using these scenes to construct dramatic, poignant canvases.

2. An artistic and societal revolution.

Romanticism took place against a backdrop of political and social upheaval. Through painting, literature and music, it portrayed the aspiration to freedom and escape, profoundly influencing future artistic movements.

A. The Traveler contemplating a sea of clouds

The Traveler Contemplating a Sea of Clouds, an 1818 work by the famous Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, is regularly highlighted as an emblematic example of Romantic painting. Often used in school textbooks and associated with poetry, this painting is an invitation to reverie. It seems natural to see the central figure as a poet seeking inspiration from the grandeur of the world. However, this interpretation may seem simplistic, as Friedrich had deeper intentions.

This painting occupies a singular place in the work of Friedrich, best known for his landscapes. The fact that a figure so dominates the composition is unusual in his work. What's more, the use of the portrait format, generally reserved for human figures, for a landscape scene is surprising. Landscape paintings are usually produced on a landscape support, i.e. one that is wider than it is tall. These distinctive choices are intriguing, affecting both the composition of the painting and its interpretation and perception by the viewer.

The man at the center of "The Traveler Contemplating a Sea of Clouds" is depicted from behind, an artistic decision that intrigues and opens up multiple interpretations. His silhouette, silhouetted against the majestic landscape, immediately catches the eye. The figure is dressed in dark hues, contrasting with the luminous, cloudy background. His attire, while dark and elegant, seems inappropriate for a mountain environment. This incongruity of dress reinforces the mystery surrounding the character.

What's more, the character's isolation accentuates the sense of solitude. He stands alone, with no other human or animal presence visible, underlining a sense of solitary contemplation. The fact that he is depicted from behind prevents any identification or understanding of his thoughts or identity. This lack of personal identification is typical of Friedrich's work, which often favors anonymity to reinforce the universality of human experience.

Moreover, the painting poses a visual challenge: although the figure invites us to explore the landscape he is contemplating, his very presence hides part of it from us. This duality creates a tension between the allure of the landscape and the barrier imposed by the figure. In this way, Friedrich uses man as a mediator between viewer and landscape, but also as a veil that conceals certain aspects of the latter, adding a layer of mystery and interpretation to the work.

B. The Raft of the Medusa

Théodore Géricault's Raft of the Medusa, with its impressive dimensions (491 × 716 cm), is considered a crucial milestone in the development of Romanticism in painting. Géricault depicts a dramatic scene of castaways on a raging raft, struggling against the hostile elements of the sea and the threatening sky. This masterful work captivates the eye with a foreground scene of death and agony, and in the center, a group staring desperately at the horizon, signaled by a man pointing toward the hope of distant help.

The structure of the composition is complex and balanced, forming two intersecting pyramids that create a powerful visual effect. The light, evocative of dawn or dusk, bathes the scene in an atmosphere of semi-darkness, heightening the drama and tension. The color palette, though limited, creates a striking contrast between the bluish tones of the sea and sky and the touches of bright red, underlined by a series of browns and ochres that sculpt the forms in a dynamic way.

The Traveler contemplating a sea of clouds

Théodore Géricault: le radeau de la Méduse. 1818-1819. Oil on canvas, 491 x 716 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre

In this work, Géricault illustrates the tragic fate of the French frigate La Méduse, which left in June 1816 to establish a colony in Senegal, accompanied by three other ships and carrying 240 people. La Méduse, under the command of Hugues Duroy de Chaumareys, an inexperienced royalist captain, ran aground on July 2 off the coast of Mauritania, a disaster due to his negligence and ignorance of the warnings of younger officers.

With the ship rapidly deteriorating, the crew was forced to evacuate. Taking refuge in a rowboat, Chaumareys left 152 people on a precarious raft, with a meagre supply of water and wine, and a promise of help. After thirteen days of agony, marked by hunger, drowning, suicide and violent conflict, only ten people survive, finally rescued by the brig L'Argus. This horrifying tale of survival and despair becomes the main subject of Géricault's painting, capturing humanity's desperate struggle against the merciless forces of nature.

Only 24 at the time of the sinking of the Méduse, Théodore Géricault began work on his painting about a year and a half later. Trained under Carle Vernet and Pierre Narcisse Guérin, two pupils of Jacques Louis David, Géricault had mastered painting techniques, but his rebellious nature led him to question academic standards.

Despite a disappointing defeat at the Prix de Rome, he traveled to Italy to study the works of masters such as Raphael, Michelangelo and Caravaggio. On his return, determined to make his mark on the Parisian art world, he set about creating a large-scale work for the Salon of 1819, destined to make a lasting impression.

Although the subject of the shipwreck of the Medusa is contemporary, it is part of a long tradition of paintings depicting human struggles against the forces of nature, a theme treated since the 17th century by artists such as Nicolas Poussin. The particularity of "Le Radeau de La Méduse" lies in its exceptional dimensions, usually reserved for biblical or mythological themes.

Géricault, while striving to distinguish himself from traditional academicism, remains faithful to the principles of historical painting, depicting the drama at its most intense. In his initial sketches, he planned to illustrate various tragic aspects of the shipwreck - the mutiny, the cannibalism, and the saving appearance of L'Argus. In the end, he opted for the poignant scene in which the survivors, having spotted L'Argus on the horizon, watch it sail away, leaving them to face an uncertain fate.

Methodical in his approach, Géricault applied classical studio techniques to the preparation of his work. He immersed himself in the testimonies of shipwreck survivors Alexandre Corréard and Jean-Baptiste Savigny, and used a model of the raft built by Valéry Touche-Lavilette, the Méduse's carpenter, embellished with wax figures to refine his anatomical studies. Despite this precision, the bodies depicted in his painting appear to be in better condition than the real victims, weakened and emaciated by experience.

Géricault's early sketches reveal the application of the classical principle of pyramidal composition, ensuring coherence and clarity. He adjusts the posture of the raft to reinforce the impression of upward movement, and gradually reduces the size of L'Argus on the horizon to accentuate the dramatic effect.

The influence of ancient sculptures, observed during his trip to Rome, is evident in the expressive power of the figures, evoking the work of Michelangelo. Géricault made the deliberate choice not to depict all the wounds and hairiness of the survivors, to maintain a certain idealism.

The man on the left, his head resting on his hand in an antique posture symbolizing despair, is a Géricault creation. His presence, alongside the body of his son, contrasts with the group of resolute, hopeful figures on the right. This juxtaposition illustrates an allegorical device, typical of the classical spirit, where despair and hope coexist in the same scene.

In his spacious studio in the Faubourg du Roule, Géricault worked with professional models, including the actor Joseph for the three black figures. He also strives for authenticity, painting the survivors Corréard and Savigny near the mast, as well as Touche-Lavilette and even relatives such as Eugène Delacroix, depicted in the center foreground, head back.

As the date of the Salon approached, Géricault noticed an empty space on the right-hand side of his painting. He quickly incorporated a corpse, adding a touch of improvisation to his meticulously crafted composition.

The work is full of realistic and sometimes crude details, such as the "son's" sagging stockings or the submerged head and pubic hair of the corpse in the foreground. To illustrate the diversity of human suffering, Géricault uses real body parts from the Beaujon hospital. His morbid studies, with their Caravaggio-inspired interplay of light and shadow, bear witness to this quest for realism.

In the final composition, Géricault combines natural lighting with an artificial light source from the left, highlighting certain bodies while others remain in darkness. This play of light accentuates the drama and theatricality of the scene.

When it was exhibited at the 1819 Salon under the title "Scène de naufrage", Géricault's work was quickly identified by the public and critics as a depiction of the survivors of the Méduse, interpreted as a veiled criticism of Captain Chaumareys' actions and, by extension, an attack on the regime of Louis XVIII.

Géricault's modern approach and powerful style were admired by some critics, while classicists criticized his technique for being too hasty. The painting becomes a point of fascination for viewers, both attracted and horrified, reflecting the darker aspects of humanity with taboo themes such as madness and cannibalism, described in the testimonies of Corréard and Savigny.

The image of a black man as an anonymous hero in the painting also provoked a strong reaction, particularly at a time when slavery was still practiced in West Africa. The depiction is seen as bold, and even as a plea for the abolition of slavery, a cause Géricault would consider further in a painting project on the slave trade.

"Le Radeau de La Méduse", marking the transition between Classicism and Romanticism, established Géricault as a bold innovator. Despite a lukewarm reception in France, the painting was a great success in England. Géricault's premature death at the age of 33 did not prevent his influence from enduring, inspiring artists such as Delacroix, who would become the leader of this new artistic era.

C. Liberty guiding the people

1. A period of marked political tension

In March 1830, the political climate deteriorated between King Charles X and the Chamber of Deputies. The King sought to re-establish the practices of the Ancien Régime, a move strongly opposed by the representatives of the people, who saw it as a threat to the progress of the French Revolution.

In the face of this opposition, Charles X took drastic measures on July 25, 1830. He restricted freedom of the press, a move designed to silence his political opponents. He also modified the already limited voting system, tightening eligibility criteria in favor of the aristocracy. He also dissolved the Chamber of Deputies, which had resisted his authority, and announced new elections for September.

These actions triggered a wave of discontent among the French population. From July 27 to 29, 1830, Parisians rose up, erecting barricades to confront the royal forces. The "Three Glorious Years" ended in victorious resistance by the people. Charles X, forced into exile outside Paris, left a political vacuum. The deputies, most of whom were monarchists at the time, including the liberals, chose to reform the constitution and establish a constitutional monarchy. Rejecting the return of Charles X, they offered the throne to Louis-Philippe, Duc d'Orléans.

Louis-Philippe accepted the title of "King of the French", marking the end of the Bourbon dynasty's reign in favor of the younger branch of Orléans. Although this historic episode is less well known today, it is still commemorated by the Colonne de Juillet, crowned by the Génie de la Liberté and bearing the names of the victims, erected on the Place de la Bastille.

2. Eugène Delacroix, the rising star of Romanticism

By 1830, Eugène Delacroix was already a recognized painter in the art world. His career began to shine from his first exhibition at the Salon in 1822, where his works attracted attention and were regularly purchased by the state. After the death of Théodore Géricault in 1824, Delacroix naturally established himself as the leading exponent of Romanticism in painting. This artistic movement favored the expression of movement and the stimulation of the viewer's emotions, in contrast to the more static style of neoclassicism.

During the Trois Glorieuses, Delacroix was not present at the barricades, busy defending the Musée du Louvre from popular unrest. He would later express a certain regret at not having been more involved in the events, as evidenced by a letter to his brother in October 1830: "Even if I did not fight for my country, I will paint it with honor".

Politically, Delacroix was in favor of a liberal monarchy that respected the rights and freedoms of the people, without adhering to republican ideas. In September 1830, he began work on his emblematic work, "La Liberté guidant le peuple", for the Salon of 1831.

3. Delacroix and his vision of a recent historical event

At its presentation in April 1831, Delacroix titled his work "Scenes of barricades", although the official catalogue announced it under the title "July 28 or Freedom guiding the people". This painting, made with the oil technique, known for its complexity and prestige, adopts a landscape format. With its imposing dimensions (2.60 meters high and 3.25 meters long), it aligns with the style of large war paintings. This deliberate decision by Delacroix aims to raise his work to the rank of major historical works, such as "The Coronation of Napoleon" by Jacques-Louis David or "The Battle of Eylau" by Antoine-Jean Gros. Through this approach, the artist highlights the historical importance of the events represented and contributes to forge an iconography that will mark the collective memory for future generations.

4. The allegorical figures of Delacroix

In Delacroix’s work, the key figures are arranged on two levels and each symbolizes a particular aspect of the event.

In the foreground

- The Swiss guard, identifiable by its red and blue uniform, symbolizes the fall of Charles X and the Ancien Régime. His death in trying to control the uprising of the people represents the failure of the monarchy.

- The cuirassier, despite his armament and mount, could not resist the power of the popular revolt.

- The naked corpse, placed far from the soldiers, embodies the anonymous sacrifice of the people in their struggle for freedom. Without clothes, he lost his social identity, but exemplified collective heroism.

Secondary

- On the left, a man armed with a sword, dressed in a beret, an apron and unshaven, represents the working class.

- Next door, another man, dressed more elegantly with a top hat and a shotgun, appears to be a bourgeois, although his wide pants are more like a worker. It symbolizes employees, like journalists or foremen.

- In front of him, a man in black trousers and blue tunic, kneeling, represents the peasants or day labourers, looking towards the female figure with the flag.

Right of table

- A young boy in a beret, wearing a cardigan and patched-up trousers, embodies the fighting youth of the people. Armed with recovered pistols and carrying a bag adorned with a coat of arms, he is a source of inspiration for the character of Gavroche at Victor Hugo.

Third plan

- The presence of a bicorne, symbol of the polytechnics, evokes the technical school created during the Revolution and mistreated by the king at that time.

The Figure of Liberty

At the heart of the canvas, emerges the emblematic figure of Liberty, the only woman on the scene, undoubtedly highlighted. She sits in the centre, elevated above others, embodying the allegory of freedom – an idea, not a being.

Lit by a bright light that distinguishes her from the ambient darkness, she walks barefoot, ready to overcome the barricade. Her left foot forward and her gaze turned towards the rebels, she seems to urge them to struggle. Despite her appearance as a girl of the people – a tanned face and a neglected outfit, revealing a bare chest and unsweetened armpits – she exudes relentless strength, dignity and resolve.

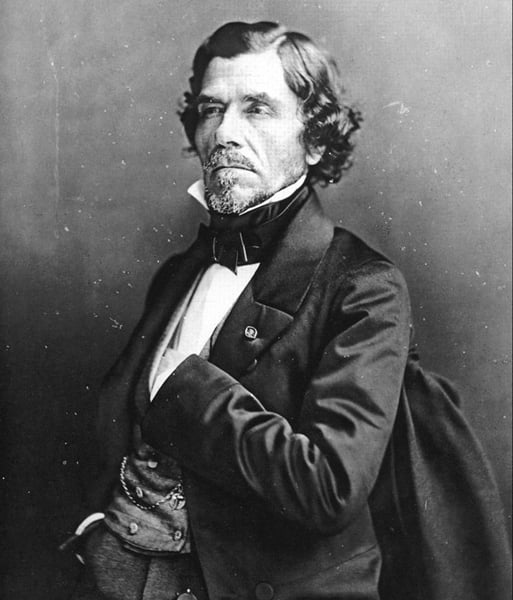

François Gérard, Charles X of France, 1825, 276 x 202 cm, oil on canvas, Château de Versailles, France

Portrait of Eugène Delacroix, 1858, photograph, Médiathèque du patrimoine, Paris, France

Eugène Delacroix: Liberty guiding the people. 1830. Oil on canvas, 260 x 325 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre

Eugène Delacroix: Liberty guiding the people. 1830. Oil on canvas, 260 x 325 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre

Contrast and Symbolism

Its posture and dress evoke the imagery of antiquity, reminiscent of Greek statues, with a profile marked by a forehead and a straight nose slightly curved – a feature of the Greek profile.

The Phrygian hat she wears is a powerful symbol of emancipation, taken up by the French revolutionaries. Close to the tricolour flag, also a symbol of the Revolution, it reinforces its message of freedom. Intriguing is the fact that she brandishes the flag with her right hand and holds her bayonet rifle with her left hand. Although this suggests a preference for the left, it is more likely that Delacroix chose this provision for symbolic reasons, with the right traditionally representing justice and virtue.

French Romanticism, much more than an artistic movement, reflected a society in search of identity and freedom. Artists of this period defied conventions by highlighting individualism, passion and the greatness of nature. They were able to capture the essence of the human soul and the torments of their time, offering a new visual language to future generations.

Romanticism is a cornerstone of French art, having left a rich and emotional legacy. He continues to inspire with his ability to capture the complexity of feelings and challenge norms, testifying to the indomitable spirit of the time.

Join us for an immersion in the passion and depth of French Romanticism. Browse our blog to explore works that cross time and continue to resonate with our personal quests of expression and emotion

#FrenchRomanticism19th, #ArtisticEmotions, #19thCenturyCulturalRevolution, #FrenchArtPassion, #RomanticLegacy, #19thCenturyArtDiscovery, #CreativeExplosion