The Renaissance in France

Welcome to our journey through the History of French Art during the Modern Times, as we explore the Renaissance in France.

Faluns of Anjou Arts

1/20/2024

In the whirlwind of the 15th century Florence, painting undergoes a major revolution. Florentine artists, fueled by the rediscovered Greco-Roman legacy, adopt an innovative approach to art, merging advanced pictorial techniques with the richness of classical mythology. This period marks a renaissance where ancient myths are revitalized and where painting transcends its traditional functions to become a conduit for intellectual reflection and aesthetic pleasure.

How did the emergence of innovative pictorial techniques and the resurgence of Greco-Roman mythology shape the artistic identity of the Florentine Renaissance, and how did these elements contribute to the construction of a new aesthetic and cultural ideal in the 15th century?

The Renaissance is a period of cultural transformation that occurred in Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries, affecting ideas, literature, arts, and sciences, as well as the economy and social sphere. It closes the medieval period and opens the modern era, with Italy and Florence as its cradle.

Innovative Painting

A-Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait

1434 marks the dawn of the Renaissance, and Jan van Eyck is one of its pioneers.With this painting, the artist transitions us from the medieval world to that of the Renaissance. It first developed in Italy and Flanders, regions with many free cities and city-states governed by their populations, or rather, by their then "elites": the trading bourgeoisie. In simple terms, leaders are elected or appointed based on their significance, i.e., their notoriety, wealth, and the influence they can wield for the good of their city.

While religion remains pervasive, the merchant bourgeoisie owes its power solely to its investment, success, and renown. In such a context, the humanism of the Renaissance could find no better breeding ground, as its philosophy places Man at the center of everything. There is thus a gradual shift from sacred art to secular art. Man can become a subject of painting.

It is in this atmosphere of change that Jan van Eyck innovates. He creates one of the very first works depicting bourgeoisie. There are precedents. But then, the bourgeoisie are represented within the context of religious paintings, in devotion, and because they are patrons wishing to show their religiosity. The Arnolfini couple does not seem to be in devotion: they stand upright and are not turned towards a religious representation. The artist here depicts Mr. and Mrs. Everyman: a bourgeois, meaning an inhabitant of a town, who is indistinguishable from other bourgeois except for the financial means to commission a portrait from a painter. More than Man as a pictorial subject, it is the individual that the artist represents. Because the Arnolfin is are painted for themselves: they are the subject of the painting.

The Moneylender and His Wife, 1514, oil on wood, 67 x 70.5 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris, France

The Moneylender and His Wife, 1514, oil on wood, 67 x 70.5 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris, France

The artist here contributes to the rise of a new genre of painting: the full-length portrait of simple individuals in their interior. Even better: individuals in their daily life, since the Arnolfinis are in their bedroom. Jan van Eyck is considered one of the inventors of genre scenes. Beyond their aesthetics, these representations are now valuable sources of information for historians about living conditions, daily life, techniques, and crafts.

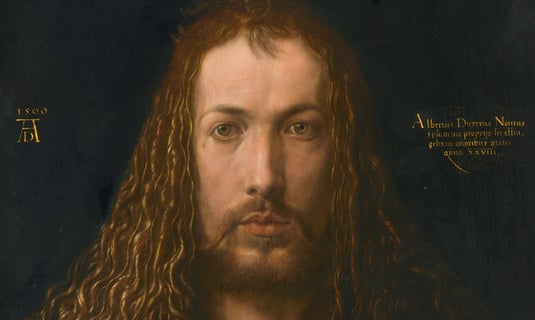

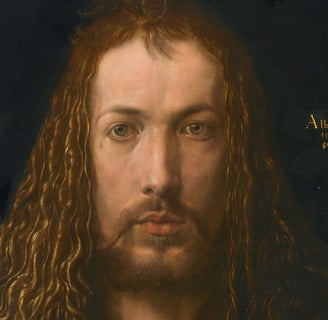

B- Self-Portrait in a Fur-Collared Robe

On a vertical panel, the principal image stands the monumental silhouette of a young man viewed frontally at half-length, with wavy hair falling over his shoulders. He is dressed in an elegant brown coat trimmed with fur, which he seems to be holding closed with his right hand.

The side lighting highlights the right side of his face, his hand, and the curls in his hair. Dashes of white, such as the top of the sleeves or a tiny part of the shirt collar, enhance the contrast with the darker areas of the painting, tempering the symmetry of the depiction.

Inscriptions stand out against the black background on either side of the face: on the left, the year 1500 and Albrecht Dürer's monogram; on the right, a Latin inscription that translates to: "I, Albrecht Dürer of Nuremberg, have painted myself in enduring colors at the age of 28."

Self-Portrait in a Fur-Collared Robe

Albrecht Dürer, a young artist from Nuremberg, initially trained in goldsmithing under his father before entering the workshop of Michael Wolgemut (1434-1519).

The self-portrait, a new genre that appeared in Italy and Northern Europe at the end of the 15th century, was not yet a common practice for artists. When they began to include themselves, it was subtly done, often sneaking into a narrative scene, usually amidst an assembly image.

One of the first masters of self-portraiture

Artist often amidst an assembly image

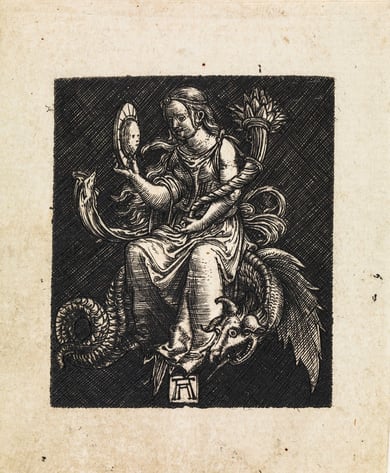

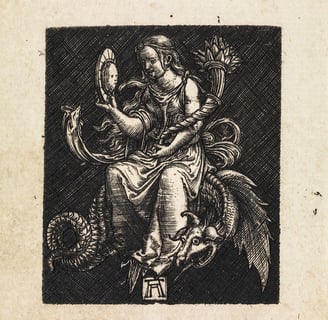

Creating a self-portrait indeed required scrutinizing one's reflection in a mirror, a practice associated with the sin of pride in Christian tradition.

This is why the self-portrait is depicted as a woman holding a mirror in an engraving image, which is part of a series dedicated to the seven deadly sins.

Image seven deadly sins

REFERENCES TO CLASSICAL CULTURE

The light draws attention to the right hand, whose gesture is intriguing. Considered during the Renaissance as indicative of an individual's personality, hands are prominently displayed in portraits, and their representation is often meaningful.

In the self-portrait from 1493 image, the hand holds a thistle, alluding to betrothal and the Passion of Christ. Here, bringing the coat over the chest, it may evoke the gesture of Roman orators.

In his famous rhetoric manual, the author Quintilian (1st century AD) recommended to "touch the chest with the fingertips, hand hollowed, to talk to oneself, addressing words of encouragement," emphasizing the importance of modesty.

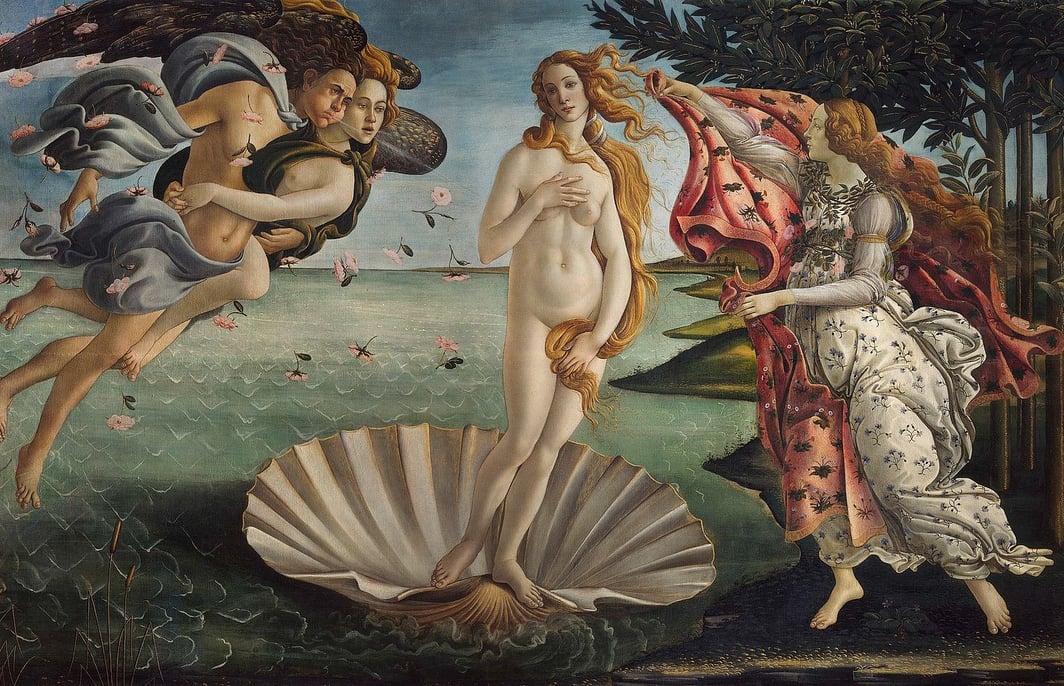

The Birth of Venus

"The Birth of Venus," a principal image, has become an icon of Italian Renaissance painting. Created in Florence, this artwork revisits a theme from Greco-Roman mythology. In Greek civilization, Aphrodite is the goddess of beauty and love, known as Venus in Roman culture. According to the myth, she is born from the sea foam and, carried on a seashell, appears on the island of Cythera. She is also the goddess of fertility. Eros (or Cupid for the Romans), the winged deity, is usually seen as her son. Botticelli, however, offers a mystical interpretation of this goddess.

AN ARTIST AT THE COURT OF LORENZO THE MAGNIFICENT

Alessandro Filipepi, better known as Sandro Botticelli, was one of the greatest Florentine painters of the late 15th century. In 1481, he was sent to Rome with the era's finest artists to decorate the Sistine Chapel. His work primarily focused on religious paintings. "The Birth of Venus," painted around 1484, stands out as it features a non-Christian subject and depicts a nude woman. Furthermore, it is painted on canvas rather than wood, which was uncommon at the time. The likely patron is Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de Medici, a cousin of Lorenzo the Magnificent and a member of the influential Medici family, who were bankers and wielded power in Florence then.

A- POETIC IMAGE OF THE GODDESS

At the composition's center is Venus, a nearly life-sized, nude young woman with long, flowing hair. She stands on a large seashell propelled by the breath of two flying figures on the left. On the right, a woman on a shoreline (the island of Cythera?) extends a pink, flower-embroidered cloak to her. The island features laurel and myrtle, symbolic plants of Venus. She appears indifferent and dreamy. Her posture, known as contrapposto, is inspired by the stance of Greek statues. The reference here is Praxiteles' "Modest Venus" (Venus of Cnidus), of which the Medici owned a Roman-era copy.

The self-portrait from 1493 image

The vulgar, carnal Venus is depicted clothed

Botticelli also drew inspiration from a poem by the humanist Angelo Poliziano, "Stanze per la giostra" ("Rooms for the Tournament"). Poliziano, a pupil of Marsilio Ficino, a humanist and tutor to Lorenzo the Magnificent's children, describes an imaginary relief on the gate of Venus' palace. This helps us identify the entwined couple as Zephyr (the regenerative spring wind) and his companion Flora. Roses escape from their mouths. To the right, the figure is possibly the Spring Hour, a nymph, daughter of Zeus, symbolizing the arrival of the beautiful season.

Botticelli's technique is not particularly innovative. Rather than focusing on the naturalistic research of his time (perspective, light), he prefers flowing lines, smooth modeling, and bright colors.

2. The Rise of Greco-Roman Mythology at the Heart of 15th Century Art in Florence

B- BOTTICELLI AND NEOPLATONISM

More important is the symbolic meaning of this work, which should be considered in the context of Neoplatonism popular at the Medici court. The thought of the Greek philosopher Plato saw a resurgence in 15th-century Florence. The city was a major cultural center of the Renaissance, enthusiastically rediscovering ancient thought. Florentine humanists, led by Marsilio Ficino, sought to build a philosophical system unifying pagan antiquity's heritage with Christian doctrine, giving birth to Neoplatonism.

Botticelli, a refined and intellectual artist, doesn't merely illustrate an ancient myth. He embraces Plato's complex interpretation of love from "The Symposium." It's a quest for absolute beauty, attainable through a multistage process: love of a beautiful body, then a beautiful soul, and finally love of knowledge, the highest form. Plato defines two principles: earthly Venus, associated with carnal love and fertility, and celestial Venus, symbolizing divine love. Although Botticelli's Venus adopts the contrapposto of antiquity, she doesn't have the proportions of a Greek statue. Her neck is longer, her shoulders narrower. Her unstable posture and melancholic expression convey a sense of grace and fragility. Her nudity is not to be interpreted erotically. Contrary to the Middle Ages, which associated the naked human body with shame and vice, the Renaissance sees physical beauty as a reflection of the soul. Botticelli's nude Venus, innocent and pure, could represent the celestial Neoplatonic Venus. In contrast, the vulgar, carnal Venus is depicted clothed. A painting by Sodoma, preserved in the Louvre, shows this dualistic conception of love: on one side, the earthly Venus, adorned, with her son Eros, representing desire; on the other, the spiritual Venus, nude, with Anteros, reciprocal love.

This duality of love (chaste and sensual) more generally expresses the idea that man and nature are born from the union of spirit and matter.

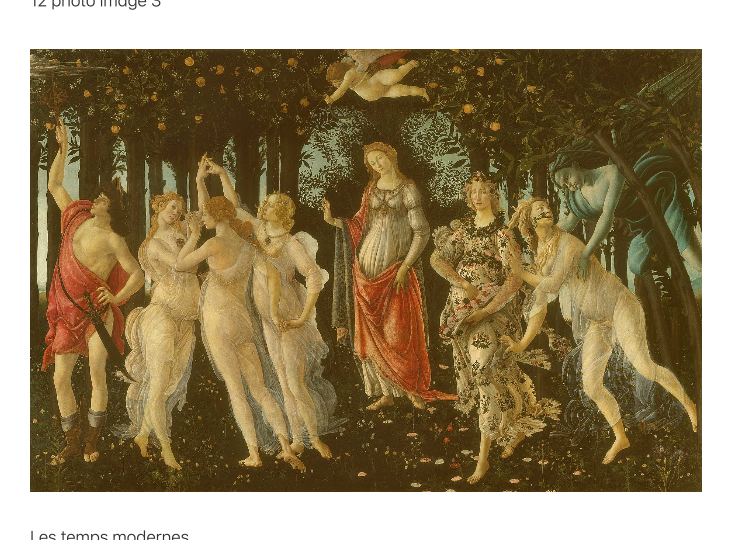

In this painting, Venus, an immaterial creature born from air (Zephyr, the divine breath) and water, incarnates into carnal Venus upon touching the earth. This second Venus is celebrated by the artist in another painting at the Uffizi Gallery, "Spring." She governs the fecundating cycle of nature and brings harmony to the universe through love. Thus, the Renaissance Neoplatonists, inspired by Botticelli, could dream of a golden age reconciling Greek humanism and Christian thought.

Image Venus of Cnidus

The Renaissance in Florence is a key period where the art of painting underwent a radical transformation, marked by the adoption of innovative techniques and the rediscovery of Greco-Roman mythology. Painters of the time, seeking realistic expression and formal perfection, integrated linear perspective and light play into their canvases. Simultaneously, mythological themes, symbols of humanist ideals and the pursuit of beauty, reclaimed a prominent place in the artistic imagination. This convergence of innovation and tradition forged a new visual language and infused a spirit of renewal that characterized the Florentine Renaissance.

The Florentine Renaissance remains a pivotal era in the history of French art, leaving behind a cultural legacy of immense richness. The audacity of the era's artists, who successfully blended the old with the new, laid the foundations for an age where art became a mirror of humanity. This period of reappropriation and innovation continues to fascinate and inspire, testifying to the timeless power of human creation.

Art and history lovers, your curiosity will find resonance in our blog dedicated to the history of French art. Join us for fascinating explorations of the Renaissance, a crucial period in artistic flourishing. Subscribe to enrich your understanding of art and participate in the celebration of its fascinating history. Join us and become part of this unforgettable cultural adventure.

Spring